This is a continuation of my series on music venue architecture. If you missed the first installment, you can find it here. These issues are prompted by the responses I have received from this request I made a few weeks ago.

I’m always curious to learn about new venues, their histories, and how their designs effect the live music performed there. This week I am studying Hamburg, Germany’s Elbphilharmonie, a concert hall designed by Herzog & de Meuron and completed in 2017.

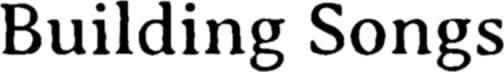

Elbphilharmonie is situated on Hamburg’s harbor—jutting out into the water on a narrow peninsula. Hamburg’s port is Europe’s fifth busiest after Rotterdam and Antwerp.1 Elbphilharmonie’s site is designed to be accessible by cargo ship. It is an odd location for a high brow cultural space, and the new construction rests on a 1960s era brick warehouse.

Notice how Herzog & de Meuron not only kept the old warehouse but extruded its form in glass. In this image, you can see how the trapezoidal forms are derived from the peninsula itself. The scale of the building is deceptive. With only water and the occasional cargo ship as neighbors, Elbphilharmonie may not seem so large; however, “the building complex accommodates a philharmonic hall, a chamber music hall, restaurants, bars, a panorama terrace with views of Hamburg and the harbour, apartments, a hotel and parking facilities.”2 The primary concert hall can seat 2,100 guests. With so many programmatic elements involved, the building’s exterior can only relay so much.

This site is outward looking—at the edge of its peninsular seat. Elbphilharmonie’s site is meant for taking in goods and seeing ships off. A concert hall is transient too. Music is temporal and live music, ephemeral. Audiences and musical movements come and go as ships do, but a concert hall is architecturally introverted. As an audience member, your only connection to the outside world is through the music. Let’s take a look inside.

Not what you might expect! There is something delightful about an unexpected space like this. The design is not too rigid it has to be symmetrical, but it is balanced audience and all. If we look closer the interior surfaces do something unexpected too. The architects call this the hall’s “acoustic crust”. It’s an ode to the stuccoed interiors of old concert halls—made modern with CNC milled panels. This also adds a quantized randomness (I first mentioned this concept in Issue #2) beneficial to the audience’s listening experience.

I will leave you with some recordings from the concert hall, so you can make your own assessment. Is the upper crust upper crusting?

Wow, what a fascinating read. Thanks for sharing this. The reveal of the site's interior was truly a jumpscare (in the best possible way). Such an architecturally ingenious design. Would love to get a slice of that upper crust!

Thank you, I’ve always been curious about this venue.